-

Biography

A trailblazer among a family of traditionalists, Koichiro Isezaki (b. 1974) preserves his renowned father’s Bizen techniques while simultaneously reimagining the ceramic with atypical forms. Early in his career, Isezaki apprenticed with American sculptor Jeff Shapiro. On returning to Japan, Isezaki established his kiln in Bizen, Okayama prefecture. He has exhibited extensively, including at the National Museum of Modern Art Crafts Gallery and the Paramita Museum, where he won the Ceramic Art Grand Prize in 2011. Most recently, Isezaki won the 2022 Japan Ceramic Society Award in recognition of his outstanding bizen artwork.

"Isezaki has a broad range of typologies – chawan (teabowls) of angular, chamfered or rounded shape; stately ridged hanaire (flower vases); torqued mizusashi (water jars) – and he infuses each of them with unique character in every piece. [...] Today, he clearly regards tradition and innovation as completely compatible: not an opposition, but a spectrum to be explored. "

– Glenn Adamson, 2025

Artist Timeline:

1974 Born in Bizen, Okayama Prefecture

1996 Graduated from the Department of Sculpture at Tokyo Zokei University, Japan

1998 Apprenticed with Jeff Shapiro in New York City

2010 Tea Ceremony - A Viewpoint on Contemporary Kogei, National Museum of Modern Art Crafts Gallery, (Tokyo)

2011 Selected to the Paramita Museum Ceramic Art Grand Prize Exhibition

2012 Received Encouragement Prize, Okayama Prefecture Development of Emerging Artists Program

2013 Solo Exhibition and lecturer in Florence, Italy

Established a new kiln in Bizen, Okayama Prefecture

2014 Received the 15th Fukutake Cultural Encouragement Prize

2019 “Bizen: From Earth and Fire, Exquisite Forms at National Museum of Modern Art Crafts Gallery (Tokyo)

Certified as a Member of Japan Kogei Association (Nihon Kogeikai)

2020 Solo Exhibition, "The Breath of Clay” at Ippodo Gallery New York

2022 Japan Ceramic Society Award

Awards and Collection:

Crafts Gallery, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Paramita Museum Ceramic Art Grand Prize Exhibition

Encouragement Award, Okayama Prefecture Development of Emerging Artists Program, City Hall of Faenza, Italy

Japan Ceramic Society Award (2022)

-

作品

-

-

Video

Koichiro Isezaki: Clay in FlowFilm & Photography: Hiromi Sato

Editing: Mayu Evans

Design: Churou Wang

Text: Glenn Adamson, Shoko Aono, Jesse Gross, Koichiro Isezai

Translation: Dai Asano, Mayu Evans

-

Director's Letter

Koichiro Isezaki’s True Courage

– Shoko Aono 2025

Ceramic artist Koichiro Isezaki does not question tradition or innovation. He does not seek to create something entirely new, rather, he holds deep respect and gratitude for earth, which has stood the test of time. Isezaki sees beauty in earth's natural expressions – his artistic passion is rooted in the desire to permanently capture the wonders of the natural world, which is evoked by the lines, shadows, and forms seen in clay.

Isezaki was born in Bizen, a region known for its pottery. Located in the southwestern part of the Japanese archipelago, it is considered one of Japan's six ancient kilns. There, he studied wood carving at university before moving to New York State, where he trained in pottery for two years. After immersing himself in a foreign culture, he returned to his hometown and experienced reverse culture shock. Today, guided by his cultural heritage, he uses Bizen clay and continues to deepen his creativity through the techniques of two kilns: anagama (cave kiln) and noborigama (climbing kiln).

Bizen ware is unglazed ceramic that is fired at high temperatures. These limiting conditions drive the artist to pursue every possible expression of the interplay between clay and fire. Notable examples include Yohen (color variation during firing), where fuel such as firewood turns to ash and coats the pieces, and Hidasuki (red stripes), where the straw that lines the box in which the pieces are placed burns during firing.

Isezaki begins his process by creating a unique blend of fine-grained, sticky rice field soil, which is harvested beneath rice paddies, and coarse, highly fire-resistant mountain soil, which is harvested from the mountains. In addition to techniques such as combing, scraping, beveling, and carving, Isezaki focuses on the Damon (hit and pattern) style, which involves forcefully striking the clay against a grooved mold.

Instead of constantly churning out new works, Isezaki commits years to selected styles, not unlike being perpetually captivated by one beautiful, natural landscape. Recently, the artist has turned his attention to the Yō (conception) style, which captures the phenomenon of expansion within a still form. A piece in the Yō style is shaped from the inside by the artist’s fingers; this internal expansion swells to the point of bursting, like the surface tension of water. Despite its gentle appearance, it is an incredibly courageous form. Yō pieces are filled with energy, the air within the form seems on the verge of expanding to the point of explosion.

The powerful yet gentle essence of Isezaki’s ceramics can be seen as a reflection of the artist’s courage in returning to his roots during his search for contemporary pottery. There is a quiet strength in going back to his hometown of Bizen after his adventures and using local materials and techniques – doing so is more challenging than proclaiming something new or creating eccentric forms, and this strength awakens a warm, quiet power in the viewer.

Isezaki’s first solo exhibition in New York in March 2020 was cut short by the onset of the pandemic. Five years later, we eagerly await the return of his beloved forms, now enriched with even greater expression, to New York City.

-

Essay: Slow Dance

Slow Dance: Kōichiro Isezaki

– Glenn Adamson 2025There are certain words, in Japanese, that contain whole philosophies. They tend to be untranslatable. One such is Yō, or Haramu (the former is the Chinese-derived on-reading of the word, the latter the native Japanese kun-reading). It can mean “conception” – as of a baby in its mother’s belly - but can also signify other types of swelling, as when a ship’s sails fill with wind, or a plant takes on moisture. More abstractly, the word can refer to the idea of consequence or implication: some new reality taking shape, right before our eyes.

This single word, then, contains so much that it is difficult to fully understand. At the same time, it is easy to see why Kōichiro Isezaki would have chosen it as the title for his most distinctive series of vessels. These are asymmetric sculptural forms which fold in on themselves, sometimes gently, almost to the point of inward collapse. They twist and sway in a slow dance, somewhat calling to mind the elegant tomb figures of the T’ang Dynasty, but with a more primordial sense of embodiment. They are as varied as people are. Some are squat, others elongated. Some he encloses in saggars during the firing, leaving them pale-skinned with just a flashing of red. Others, especially those positioned near the kiln’s firebox, are completely saturated in dark ashfall glaze.

From a technical point of view, the Yō series showcases Isezaki’s complete mastery of the Bizen ceramic tradition. He works in a studio in Imbe, Okayama Prefecture, which was also used by his father Jun (designated a Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Property, or “Living National Treasure”). The workshop has three anagama kilns of different lengths – five, ten, and fifteen meters – and different slopes, each of which produces its own particular effects due to its unique shape and the speed of heat’s passage. The largest of these kilns requires twelve days and some 7500 pieces of akamatsu (red pine) wood to fire. This duration and intensity seems to infuse the objects with a lasting sense of heat and energy; of all ceramic types, none embody the raw force of transmutation more than Bizen yaki.

Additional marking is achieved using the hidasuki technique, in which pounded rice straw (using a varietal grown for sake, not for eating) is wrapped or placed against the pot. As it burns away in the kiln, it produces a vivid red scorch on the clay surface. Isezaki is especially skilled with this technique, using it to wonderfully painterly effect. He often sets a pot on a cushion of straw to give it a fiery base, sometimes stretching the coloration further up the vessel’s side. In other pieces he employs the traditional Bizen technique of wrapping the object in a crisscross pattern of straw, setting up a dynamic counterpoint to the rhythms of the pot itself.And what rhythms they are. Isezaki has a broad range of typologies – chawan (teabowls) of angular, chamfered or rounded shape; stately ridged hanaire (flower vases); torqued mizusashi (water jars) – and he infuses each of them with unique character in every piece. The present exhibition at Ippodo Gallery features a new idea: closed-off hemispherical bowls and taller globular vases, corrugated with thick ribs across their tops. Each of these pieces has a pronounced rift in it, a motif more geological than artisanal, which admits a partial view into its dark interior. One of the great pleasures of the show is its elastic treatment of the established Bizen repertoire. In some pieces he stays close to his roots, while in others he plows new ground. He has not always stayed close to home – he spent two influential years in the Hudson Valley studio of Jeff Shapiro, a former apprentice of Jun Isezaki and one of America’s great exponents of woodfired ceramics, who encouraged Kōichiro to find his own individual voice. Today, he clearly regards tradition and innovation as completely compatible: not an opposition, but a spectrum to be explored.

All this makes for an extremely rich backdrop, but there is no doubt that the Yō series takes center stage. To make these pieces, Isezaki uses a sticky clay sourced from rice paddies – a material with a strong personality, as he says, “easy-going and carefree” – which allows him to realize soft, voluminous contours. It is worth noting that he once studied wood carving, a subtractive technique that lends itself well to shaping irregular volumes. The influence of that other medium may possibly be felt in the taut yet unpredictable contours of these vessels. They combine the subtle contrapposto of classical sculpture with the imaginative abstraction of a Brancusi or a Henry Moore. Unquestionably, however, these forms evolve from Isezaki’s profound understanding of ceramics, a medium in which the conversation between interior and exterior is always vital. “Which decides the form, the inside or outside?,” Isezaki is sometimes asked, to which he responds: “well, both come simultaneously.” As he twists and folds the pliant clay, it seems to quicken into something like sentience; the vessel is like an infant in the first moment of consciousness, drawing in a first breath.

The title of the series, then, is well chosen. These works do materialize the idea of “conception,” both in the sense of a new idea and a newborn life. Like other phenomena associated with the word Yō – those billowing sails and unfurling leaves – these objects pulse with the generative energies of nature. The elements of earth, water, and fire course through his creations: forms of potency so vast, so ancient, that they dwarf our humble human actions. The greatest ceramic artists – and Isezaki is certainly one of them – find new ways to channel these forces while also remaining respectful of them. It is a fine balance, as rigorously demanding as a ballet, as exploratory as avant garde choreography. Take up one of his vessels in your hands, and feel its surprising lightness. Feel yourself becoming its dance partner, as he has been. For poise, for strength, for sheer creativity, you will never find a more consummate performer than Kōichiro Isezaki.

-

展覧会情報

-

Koichiro Isezaki: Clay in Flow

2025年9月11日 - 10月11日Exhibition opens Thursday, September 11, 2025 Opening Reception at 35 N Moore Street, TriBeCa : September 11, 5–8 ...Read more -

Magic of the Tea Bowl

Volume 3 2023年6月8日 - 7月31日Magic of the Tea Bowl (Vol.3) June 2023 The Japanese tea ceremony was first established during the sixteenth century and...Read more -

Extreme Surfaces: Cutting Edge Kogei

Ippodo Gallery's Premiere at Design Miami 2022 + New Year Exhibition 2022年11月30日 - 2023年2月16日Ippodo Galleryis a pioneering kogei -focused gallery based in Tokyo and New York. Our mission is to honor the living tra...Read more -

Magic of the Tea Bowl

Volume 2 2022年6月2日 - 7月7日Magic of the Tea Bowl (Vol.2) April 2022 The Japanese tea ceremony was first established during the 16th century and has...Read more -

The Breath of Clay

The Life of Koichiro Isezaki's Contemporary Bizen 2020年3月12日 - 4月16日Time seems to pass slowly in this small village. Set among the greenery of the surrounding mountains, passing along a ro...Read more

-

-

Events

-

Artist Talk and Opening Reception, Koichiro Isezaki: Clay in Flow

2025年9月11日We are delighted to welcome the artist Koichiro Isezaki, who travels from Japan, to celebrate his second New York solo exhibition. The artist's mentor Jeff...Read more -

Opening Reception - June 13, 6-8 PM

Magic of the Tea Bowl Vol.3 2023年6月13日Please join us on Tuesday, June 13th, from 6 PM to 8 PM EST at Ippodo Gallery (32 E 67th Street, New York, 10065). Ippodo...Read more -

Design Miami 2022

Extreme Surfaces: Cutting Edge Kogei 2022年11月30日 - 12月4日Design Miami 2022Read more -

Opening Reception - June 2 5-8pm

Magic of the Tea Bowl Vol. 2 2022年6月2日Ippodo Gallery is pleased to present another series of Magic of the Tea Bowl – Volume 2, an exhibition of tea bowls by seventeen respected...Read more -

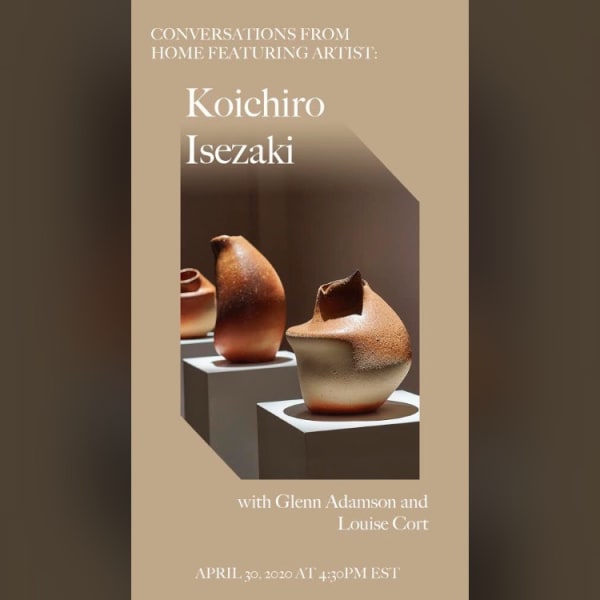

Conversations from Home Vol.1

Koichiro Isezaki x Louise Cort x Glenn Adamson 2020年4月30日Featuring: Koichiro Isezaki - Ceramic artist Louise Cort - Craft Historian and Curator emerita for ceramics at the Freer and Sackler, Smithsonian Glenn Adamson -...Read more

-

-

Blog

-

Slow Dance: Koichiro Isezaki

Contributing Essay by Glenn Adamson 2025年7月24日– Glenn Adamson, 2025 There are certain words, in Japanese, that contain whole philosophies. They tend to be untranslatable. One such is Yō , or...Read more -

Studio Visit: Koichiro Isezaki

Magic of the Tea Bowl Volume III 2023年7月3日A ceramicist working in the tradition of Bizen , and the son of the Living National Treasure of Bizen —one of Japan's six great historical...Read more -

Altered Forms

Ribbing, Faceting, and Molding 2020年12月22日Since the beginning, ceramicists have experimented with form. Altering a thrown object (done on the potter’s wheel) or adding to the piece is more common...Read more -

A Slender Silhouette:

On Ippodo Gallery’s Tall Forms 2020年12月8日Koichiro Isezaki, Yo, C19718 Placed in a sagger and wrapped carefully in rice straw, each vessel made by Isezaki emerges from the kiln with their...Read more

-